(Cover Story)

At five minutes before nine the warning bell clanged, and the chattering

parliamentarians in the lobby began to file into the House to take

their seats. Precisely on the hour, a voice raised the traditional cry

"Mistah Speakah," and the legislators froze as a bemedaled attendant

solemnly descended the nine red-carpeted steps into the well of the

House and laid a golden mace on the table separating the government

front benches from those of the opposition. After a prayer calling down

God's protection on the nation and Queen Elizabeth II, the Speaker, in

his English-accented English, called "Odah, odah," and the debate

began. Scarcely had it got into full swing when a proud, ascetic figure

strolled slowly toward the government bench and all eyes converged on

the ebony face of Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, O.B.E., K.B.E.,

C.B.E., LL.D., Prime Minister of Nigeria.

Along with its echoes of Britain's Westminster, the legislature over

which Sir Abubakar presided last week had some of the flavor of a

Pan-African Congress. On its benches tall, haughty Hausas, splendidly

robed in green and scarlet, sat amongst volatile Ibos draped in white

and azure gowns. Across the aisle were Yoruba tribesmen wrapped in

gold, yellow and orange with little porkpie beanies on their heads.

Between them, they constituted one of the world's noisiest Parliaments.

Each speaker was greeted with cries of "Heah, heah" from his friends

and derisory shouts of "Sit down, you wretched fool" from his foes;

from the rostrum came the perennial plea for "Odah, odah!" But somehow,

through the din, the nation's problems got discussed and decided.

In the hurly-burly of 1960's African avalanche of freedom, Nigeria's

impressive demonstration of democracy's workability in Africa is too

often overlooked. Next-to-newest of the 18 nations* to win independence

this year (see p. 23), Nigeria entered the world community without

noisy birthpangs or ominous warnings of its determination to avenge

ancient wrongs. Since moderation and common sense are not the stuff

that headlines are made of, the world's eyes slid past Nigeria to focus

worriedly on the imperialistic elbowings of Ghana's Nkrumah, on the

heedless plunge into Marxism taken by Guinea's Sékou Touré

and above all, on the bloody chaos in the Congo.

In the long run, the most important and enduring face of Africa might

well prove to be that presented by Nigeria. Where so many of its

neighbors have shaken off colonialism only to sink into strongman

rule. Nigeria not only preaches but practices the dignity of the

individual. And where such other islands of order in Africa as Liberia.

Togo and the former French Congo lack the size and power to overbalance

thrusting Ghana and Guinea (combined population: 8,665,000), the

Federation of Nigeria stands a giant among Lilliputians; last October,

when Nigeria's 40 million people got their independence, the free

population of Black Africa jumped 50%. Backed by such numbers,

Nigeria's sober voice urging the steady, cautious way to prosperity and

national greatness seems destined to exert ever-rising influence in emergent Africa.

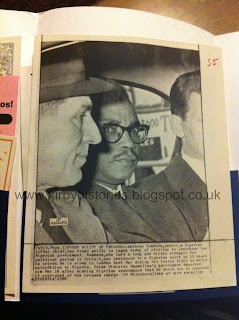

The Perfect Victorian. No man better symbolizes the strengths and hopes

of independent Nigeria than Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (pronounced

Bah-lay-wah). At 47, he is slight of figure (5 ft. 8½ in., 136 Ibs.),

and his wispy mustache and greying, crew-cut beard make him look older

than he is. Reserved and unassuming, he is a rare bird in a land famed

for flamboyant politicians, was once described by an African magazine

as a "turtledove among falcons."

But for all his lack of drama, Sir Abubakar is an astute and impressive

statesman. His rolling, resonant oratory and superb command of English

have won him the nickname "The Golden Voice."

For his crucial role in Nigeria's advance to independence, Britain has

heaped him with honors and his native admirers hail him as "The Black

Rock of Nigeria." (As a devout Moslem, the title he prizes most is that

of alhaji—one who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca.) In his drive to

lift his backward land into the 20th century, Balewa's piercing eyes

exude calm and sureness, and he rarely speaks in anger. "He is," says a

longtime British acquaintance, "perhaps the perfect Victorian

gentleman. He simply will not be rushed."

Hershey Bars & Chickens. Sprawled along 580 miles of the choppy Gulf of

Guinea, Sir Abubakar's Nigeria is a ragged rectangle the size of Texas

and Oklahoma combined. Just behind the beach, guarded by a great green

mangrove wall, lie sweltering swamps—and the mosquitoes whose deadly

bite kept white men from settling Nigeria as they did Algeria, Kenya

and the Rhodesias.* Beyond the swamps is the thick layer of tangled

rain forest, where the natives pick cocoa pods for the world's

chocolate factories and gather oil palms for the big soap firms. Then

comes the undulating grass country, rising in the north to the crusty,

arid, mile-high floor and then to the hot Sahara's edge, where by day

nomadic cattle herders bow to Mecca and muffle their faces against the

sun and grit-filled harmattan winds with robes that keep out the bitter

chill when the sun goes down.

Scattered across this diverse land, Nigeria's cities throb with the

vigor of noisy commerce and the color of exotic dyes. In the federal

capital of Lagos (pronounced Lay-gahs), where gleaming buildings rise

among the slums, the streets are a cacophony of honking autos and a

torrent of heedless jaywalkers. Lagos' open-air market is a constant

melee: picking their way through tall piles of blinding indigo or

scarlet cloth, vast platters of red peppers on bright green leaves, and

mounds of white salt, hordes of shrieking women peddle alum, alarm

clocks, Hershey bars, live chickens, hair tonic—all from overloaded

trays atop their heads.

Around the Y. But the central fact of Nigerian politics is not a clash

between townsman and bush dweller. It is, instead, racial and religious

rivalries pointed up by the mighty Y that is stamped across Nigeria's

face (see map) by two great rivers—the winding Benue that pours from

the cloud-ringed Camerounian mountains in the east, and the majestic

Niger that comes in from the west to join the Benue in a single mighty

stream running south to the Gulf of Guinea.

Under the Y's left arm, in the Western Region (pop. 8,000,000), live the

most advanced of all Nigerians—the Yoruba tribesmen, who worship 400

different deities, including Shango, god of thunder, and boast a

centuries-old tradition of political organization.

Under the right arm of the Y is the heavily forested Eastern Region

(pop. 9,000,000), home of the Ibo. a fiercely independent people, half

Christian, half pagan, and known, because of their get-up-and-go, as

"the Jews of Africa."

Black Africa's first TV station and Nigeria's first university are in

the Western capital of Ibadan, where three-quarters of a million people

cluster noisily under a sea of tin roofs. Between them, the Yoruba West

and bustling Ibo East dominate Nigeria's commerce and furnish most of

the country's bureaucrats. But the real weight of the nation rests on

the top of the Y. Here, in the Northern Region, live close to 20

million people, mostly Moslems, who still remember the jihad (holy

war), in which, 156 years ago, the Fulani horsemen of Imam Othman dan

Fodio overwhelmed the original Hausa inhabitants. Though it is still an

essentially feudal society in which Hausa-speaking masses are ruled by

stern Fulani emirs, the North today, by sheer weight of numbers,

controls Nigeria's federal House of Representatives and, in the person

of Sir Abubakar, lords it over the bright brats of the South.

To the New World. It was in the North too that Nigeria's written history

began—in the walled-caravan center of Kano, whose chronicles date back

to A.D. 960 and whose big, modern airport today is one of the world's

busiest. For coastal Nigeria the ages passed without written record

until the late 15th century, when Portuguese adventurers sailed and

marched up the creeks to Benin, whose 16th and 17th century bronzes

(some of which depict Portuguese traders) are now among Africa's most

treasured art objects. To the Portuguese—and the English who

eventually displaced them—Nigeria's most valuable commodity was its

people. Between 1562 (when Sir John Hawkins carried Britain's first

slave cargo to Haiti) and 1862 (when the last Nigerian was sold in the

U.S. South), Nigeria's chiefs sold so many hundreds of thousands of

their countrymen into slavery in the New World that Nigeria became

known as the Slave Coast.

With slavery's passing and the coming of the Industrial Revolution,

Britain's interest in Nigeria shifted from people to palm oil. To get

the oil, British trading companies began to penetrate the interior of

Nigeria—and after them came the Union Jack. By 1903, when Sir

Frederick Lugard (later Lord Lugard) began his campaigns against the

Northern emirs, British rule in Nigeria was an accepted international

fact. But even yet no one conceived of northern and southern Nigeria

as having anything but a geographical connection; the word Nigeria

itself was coined by a London Times contributor named Flora Shaw—who

later became Lady Lugard. Not until 1914, when Lugard, one of Britain's

great colonial administrators, took over as Governor General of both

North and South, was modern Nigeria born.

A Matter of Chance. The man who rules Nigeria today is two years older

than his country. He was born simply Abubakar, the child of Yakubu, a

minor official in the regime of the emir of Bauchi. (According to

northern custom, he later added to his given name that of his

village—Tafawa Balewa.) Though Abubakar was not of the mighty

Fulani—his family belonged to the Geri tribe—his father's position

won him the rare privilege of schooling in a region almost totally

illiterate. After secondary school he was even able to get into Katsina

Teachers' Training College, normally open only to sons of the northern

feudal elite.

Armed with his rare education, Abubakar returned to the windswept

Bauchi Plateau and settled down on the staff of a Boys Middle School;

he was a born teacher, and might have spent his life there except for a

chance remark by a friend, who said that no northern Nigerian had ever

passed the examination for a Senior Teacher's Certificate. Piqued by

this reflection on northern intelligence, Abubakar took the exam and,

to the astonishment of southern colleagues, passed it with ease.

Impressed, London University's Institute of Education granted him a

scholarship in 1945.

Ferment at Home. Uninterested in politics, Abubakar stuck to his books,

never met such hot-eyed young nationalists as Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah and

Kenya's Jomo Kenyatta, who were also in London then. When the BBC

sought a Nigerian to read Nigeria's new 1946 constitution on its

overseas service, Abubakar willingly took the job but had, he later

confessed, not the slightest idea what the document he had read was all

about.

Back home, there were plenty of noisy young men who did. Noisiest was

the flamboyant Nnamde ("Zik") Azikiwe, a nimble Ibo spellbinder who had

spent nine years in the U.S. working as a coal miner, professional

boxer and gatherer of university degrees (Lincoln University, the

University of Pennsylvania). Returning home, he became the loudest

advocate of an independent, united Nigeria. Under the rising pressure,

the British agreed to set up—as "advisory" bodies only—local Houses

of Assembly in all three regions, plus a federal legislative council.

A Mere Intention. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was hardly back from his year

in London when the northern emirs, suddenly confronted with the need to

find literate occupants for the northern seats in the federal assembly,

pressed him into service. Like the emirs themselves, Abubakar started

off with the fear that in a unified Nigeria the backward North itself

would be swamped by the vigorous, better educated South. "Nigerian

unity," he told the assembly, "is only a British intention for the

country. It is artificial, and ends outside this chamber!"

With Zik & Co. sowing the seeds of rebellion in the South, the days of

British rule in Nigeria were clearly numbered. But at conference after

conference, the bemused British could only sit apart and smile as the

Africans themselves delayed independence by interregional quibbling.

Not until 1951 did the shape of the ultimate solution begin to appear:

in return for accepting a federal legislature with real power, the

North would get as many seats as the East and West combined.

A Rebel's Conversion. By then Nigerian politics had taken on a permanent

three-way stretch. In the Ibo East, Zik's National Council of Nigeria

and the Cameroons held sway. In the West, the Action Group, headed by

shrewd, stodgy Chief Obafemi Awolowo (pronounced Ah-Wo-lo-wo), spoke

for the Yoruba people. Northern power then (as now) meant tall, solemn

Alhaji Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna (commander) of Sokoto and boss of

the Northern Peoples Congress.

Since the Sardauna had no interest in settling in Lagos among the

"southern barbarians," Abubakar became the protector of northern

interests in the capital. Grudgingly, he went along with federal unity

to the extent of becoming Minister of Works. "From the start he was the

best minister of them all," recalls a British civil servant. "He did

his homework and sent his paperwork through swiftly." But he remained a

northerner, not a Nigerian.

A Single Pride. His moment of enlightenment came in 1955, when Abubakar

journeyed to the U.S. to find out whether what the U.S. had done to

develop water transport on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers could be

applied to the sand-clogged Niger. One night, as he sat in a Manhattan

hotel room, he got to thinking about what he had seen in the U.S. His

thoughts as he recalls them: 'In less than 200 years, this great

country was welded together by people of so many different backgrounds.

They built a mighty nation and had forgotten where they came from and

who their ancestors were. They had pride in only one thing —their

American citizenship." That night he wrote to a friend in Nigeria:

"Look, I am a changed man from today. Until now I never really believed

Nigeria could be one united country. But if the Americans could do it,

so can we."

Day of Freedom. With that, a united, independent Nigeria became only a

matter of constitution writing and tidying up the details of

transferring power. The British, their long and successful work of

tutoring done, were ready. In 1957 Sir Abubakar stepped in as Nigeria's

first Prime Minister, to prepare the nation for full freedom. Last

October 1, as drums rumbled, guns blared and exuberant citizens

gleefully shuffled through the high-life dance, Nigeria's green and

white banner rose over Lagos in place of the Union Jack.

Along with independence. Nigeria acquired one of the most stable and

genuinely representative governments in Africa. To ensure the votes

necessary to push through his programs, Abubakar brought Zik's N.C.N.C.

into coalition with his own Northern Peoples Congress. As payment,

longtime Firebrand Zik unpredictably accepted the ceremonial job of

governor general. Chief Awolowo resigned himself to the role of

Opposition leader.

Time & Tolerance. Despite the favorable omens under which Nigeria was

born, the burdens on Sir Abubakar's slender shoulders are awesome. The

diversity that gives Nigeria's government a kind of built-in system of

checks and balances also poses the ever-present threat of

fragmentation; to weld Nigeria's 250 major tribes with as many

languages into a single, indivisible nation will require not only time

but tolerance. With only 175,000 pupils receiving secondary education,

schools are desperately needed. In terms of university graduates,

Nigeria is better off than the Congo, but there are still only 532

qualified Nigerian doctors, 644 lawyers, 20 graduate engineers. Awolowo

and others are demanding that Abubakar throw out the British holdovers

who still occupy half of Nigeria's senior civil service posts; yet, as

Abubakar points out, "Nigerianization" of the civil service cannot sensibly

be completed until enough Africans themselves can be trained.

Economically, Nigeria is a "have" nation by African standards, is close

to self-sufficiency in food. But with a per capita income of only $84,

capital is lacking to move the economy beyond its present agricultural

base. Tin, columbite (for jet-engine alloys) and coal are all being

exported, but there is no money to develop the lead, zinc and iron ore

that have been found in quantity. Abubakar dreams of building West

Africa's first steel mill and a huge dam on the Niger. But the big hope

is oil. After 25 years, Shell finally hit a gusher in 1956, figures the

Niger Delta swamps contain reserves of perhaps one billion barrels.

The Cold Stare. Within Nigeria's brand-new government, corruption

flourishes—to the chagrin of Sir Abubakar, who startles his colleagues

by actually handing back the surplus of his expense-account money when

he returns from a trip abroad. And where honesty exists, talent is

often lacking. To get results, Sir Abubakar, normally mild and patient,

hounds his ministers, occasionally displaying to inept underlings a

towering temper never seen in public. An error can bring simply a long,

cold stare; it can also bring an explosion, as it did recently when a

minister tried to justify an obvious goof. "That is quite enough,"

snapped the Prime Minister. "Shut up and get out!"

To avoid wasting time in the horrendous Lagos traffic—where auto trips

are measured in the number of cigarettes consumed rather than in

minutes—Sir Abubakar lives in a modern, two-story cement house near

his office with his wife and nine children—plus the swarming families

of his chauffeur and police orderly. In the Moslem tradition, his wife

does not appear in public; for formal dinner parties, Abubakar borrows

the Irish wife of a fellow minister to act as hostess. Up for prayers

at 6:30, Abubakar breakfasts in time to arrive at his office precisely

at 8:15, heads home again at 2:15 in the afternoon with enough folders

full of state papers to keep him busy until bedtime. Once a heavy

smoker, Abubakar swore off after his 1957 pilgrimage to Mecca, now

combats the tensions of his job by chewing the bitter kola nuts that he

keeps in the pocket of his long white riga.

The Christian Virtues. In his public contacts, Abubakar is quiet and

self-effacing, but in Parliament he has lately begun to vary his usual

restrained tactics. Fortnight ago, when the House of Representatives

was debating a mutual defense pact that would allow Britain's R.A.F. to

retain facilities at Nigerian airfields, Opposition Leader Awolowo,

intent on embarrassing the government, cried out in outrage that the

proposed pact was a "swindle" that would automatically involve Nigeria

in war if Britain got in trouble. In his rich, rolling bass, Sir

Abubakar fired back: "I have always regarded the leader of the

Opposition as a good Christian; in Christianity as in Islam, it is a

sin to tell a lie." While Awolowo stared grimly at the ceiling, the

Assembly ratified the treaty by a vote of 166 to 38.

Last week, on the heels of the defense-treaty debate, the avant-garde of

Nigeria's young intellectuals were sneering at Abubakar's open

admiration and affection for Britain. And all across Black Africa, the

smart set of extreme nationalism accused Abubakar of the African

version of Uncle Tomism. They were distressed by the instinctive

anti-Communism that prevents him from joining in the delightful game of

giving the "colonialists" the shivers by cozying up to Moscow. (At

Nigeria's independence celebrations, when Russia's Jakob Malik cheerily

announced that the Soviets planned to open a Lagos embassy immediately,

Abubakar bluntly told him: "As a diplomat, you must understand that

things are not done that way. You must submit an application for

diplomatic relations, and we shall judge it on its merits.") Above all,

the extremists are shocked that Abubakar can barely conceal his

contempt for showboating Kwame Nkrumah and his schemes for Pan-African

unification, instead urges that for the time being, African cooperation

be limited to such practical steps as technical and cultural exchanges,

a common U.N. front and, perhaps, economic agreements.

But for all of Ghana's contempt for its bigger Johnny-come-lately rival,

Nigeria, less than two months after winning its independence, is on its

way to becoming one of the major forces in Africa. Nigeria's dynamic

U.N. Ambassador Jaja Wachuku is chairman of Dag Hammarskjold's Congo

Conciliation Commission. A number of African nations, notably those of

the French Community, are beginning to sidle up to Nigeria in visible

relief at the emergence of a counterweight to the firebrands of Ghana

and Guinea. And Abubakar himself has begun the wheeling and dealing

abroad expected of a sovereign nation's leader; at last week's end he

headed for London to mull over Commonwealth problems with Harold

Macmillan, stopped off en route to discuss the Algerian war with Arab

leaders in Tunis.

Like everything else about him, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa's basic

foreign policy principles are unpretentious: "We consider it wrong for

the Federal Government to associate itself as a matter of routine with

any of the power blocs . . . Our policies will be founded on Nigeria's

interests and will be consistent with the moral and democratic

principles on which our constitution is based." If Nigeria lives up to

his words, Africa and the world will have cause to be grateful.

*The 18th, Mauritania, becomes independent this week.

*In tribute to this involuntary ally against colonialism, the flag of

Nigeria's Western Region today bears a symbolic mosquito.